A Much More Boring Inspiration

Here she is on Unbroken, which opens in the UK today. If you don’t know the plot of the film, the whole review is well worth a read, but the theology she engages in here rivals much you’ll find on the rest of that site:

Sarah Pulliam Bailey wrote about some of the expected Christian backlash around the fact that the film takes the final section of the book—which recounts [main character Louie] Zamperini’s conversion and move to forgive his [Japanese prison camp] captors—and instead of dramatizing it, writes about it in a lengthy, respectful series of the sorts of title cards you typically see at the end of a “true story” film.

I’ll confess that I rolled my eyes a little bit when I first read about the expected controversy, because one of the most common criticisms leveled against biopics of any sort is that they left something out—and the thing about making a feature film out of any book-length work is that you have to pick and choose what works best on screen, what makes for a nicely-crafted story arc with a beginning, middle, and end. Plus, it is my experience that some Christian moviegoers tend to assume that any omission or alteration of explicit faith material is enacted as a kind of calculated aggression against them and their faith, rather than for various other reasons—craft, marketability, storytelling, simple lack of knowledge, or whatever. And Unbroken displays no anti-faith bias.

But now that I’ve seen it, I agree: the film still suffers from this omission.

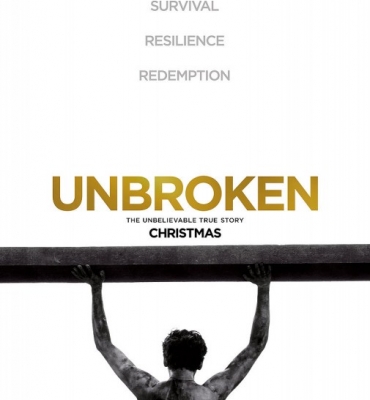

It’s being billed as an “inspirational” film, but the most important scene—the image that’s being used on movie posters—crystallizes what gets Zamperini through his ordeal. It isn’t faith—that comes later. Rather, it’s a sort of grit-your-teeth endurance borne out of hatred for your enemy. It comes from being so determined to master your enemy that you manage to perform great feats of will and strength and outlast him. This is made explicit in comments from one of the film’s characters, and it goes unchallenged throughout the film.

...

So what I fear is that audiences will watch the film and walk away saying to one another, “Wasn’t that inspiring?”—without asking, what did it inspire you to?

The story of resilience and outlasting and will and determination is scored and shot, acted and directed and sometimes visually striking, and what it inspires you to do is hate your enemies so hard that you can prove you’re better by them by making it past the finish line.

...

Sometimes I get the uneasy feeling that this is how we Christians conceive of what Jesus inspires us to do, which is to suffer and die, only to be resurrected on the third day and yell a cosmic Ha, you lose at the forces of evil. Instead of things like do what is crazy, pick up your cross, sacrifice for others, consider others better than yourself, give, give, give and love with no expectation of return.

Sometimes the swagger in our voices when we talk about the gospel, or talk about “those people” and how they are plotting our ruin, sounds less about sacrifice and letting go of what we think we deserve, and more about winning the game and proving we’re the best.

Here is what Jesus said that actually changed Zamperini’s life and inspired him, as translated by Eugene Peterson:

Here’s another old saying that deserves a second look: “Eye for eye, tooth for tooth.” Is that going to get us anywhere? Here’s what I propose: “Don’t hit back at all.” If someone strikes you, stand there and take it. If someone drags you into court and sues for the shirt off your back, giftwrap your best coat and make a present of it. And if someone takes unfair advantage of you, use the occasion to practice the servant life. No more tit-for-tat stuff. Live generously.

You’re familiar with the old written law, “Love your friend,” and its unwritten companion, “Hate your enemy.” I’m challenging that. I’m telling you to love your enemies. Let them bring out the best in you, not the worst. When someone gives you a hard time, respond with the energies of prayer, for then you are working out of your true selves, your God-created selves. This is what God does. He gives his best—the sun to warm and the rain to nourish—to everyone, regardless: the good and bad, the nice and nasty. If all you do is love the lovable, do you expect a bonus? Anybody can do that. If you simply say hello to those who greet you, do you expect a medal? Any run-of-the-mill sinner does that.

The titles that run after the visual story ends contradict the impression given by most of the movie’s two-hour runtime—but text, I fear, cannot stand up to the lushly shot, orchestrally scored images. So what is actually most inspiring about Zamperini’s story—not that he won through the force of his own will, but that he then turned around and reciprocated with love—should happen in the third act. But what sticks with you is the images.

...

So in the end, I’m mostly frustrated that once again a movie is getting marketed at Christians, and will make a ton of money from them, that is probably going to be an exercise in missing the point. And my point here is not that “the Christian part” was removed because of some kind of rumored bias against it (it is not), but that it hollowed out the revolutionary story and left a much more boring inspiration in its place, some more about the indomitable human spirit and so on, which we’ve seen before.

Here is what I’d suggest: If you want to, go see Unbroken. Be inspired. Zamperini was an incredible man. But when you leave, talk to the people you went to the movie with. Talk about what it inspired you to do. Let that be what Zamperini’s life (and Jesus’ words) are really about: not winning, not defiance, not coming out on top at the end of the day, but the humble revolution of living generously and loving your enemies, especially when nobody notices and it makes no sense.

Our world, and our churches, could use a lot more of that right now.

Brilliant.