Andy Stanley and Dunbar Dynamics

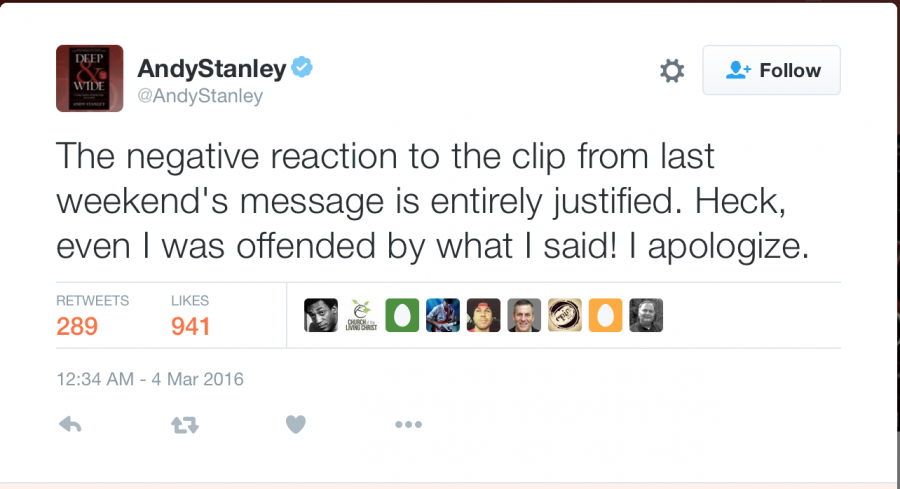

This generated a lot of pushback, and Stanley later went on Twitter to apologize:

I happened to be preaching on friendship the same Sunday Stanley preached this message, and in doing so made reference to the Dunbar Number. Named after anthropologist Robin Dunbar, this is the theory that human beings can only maintain friendships with around 150 people; as a consequence, 150 is the numerical point at which many human activities are organised. As examples, the military is organised around companies of about 150 men, iron age villages grew to a maximum of about 150 people before ‘planting’ a new village, and 150 is close to the average number of friends people have on Facebook. It seems we just don’t have the mental capacity to maintain friendship with more than about 150 people.

The Dunbar number operates on a rough rule of threes. Working upwards from 150, we might have about 500 acquaintances – people we would say hello to if we passed them on the street. Beyond that, there might be about 1,500 faces we could just about put a name to, but wouldn’t feel any close connection with. Working downwards, we might have about 50 friends who feel like ‘real’ friends – the people we would actively choose to socialise with. Below that we might have a dozen or so intimate friends, and then perhaps three or four people we’d trust with anything.

In military terminology these natural organizational boundaries are:

• The fireteam: 4 people

• The section: 8-13 people

• The platoon: 26-55 people

• The company: 2-8 platoons, or 80-225 people

• The battalion: 2-6 companies, or 300-1,300 people

• The regiment: 2+ battalions, or 3-5,000 people

Interestingly, even Jesus seemed to operate according to this theory. He had his group of close friends – the twelve – and within that his intimate circle of Peter, James and John. But he also had the 120, and the 500:

In those days Peter stood up among the brothers (the company of persons was in all about 120). (Acts 1:15)

For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have fallen asleep. (1 Cor. 15:3-6)

If 150 is about the maximum number of people we can have a meaningful relationship with then it is unsurprising if most church-goers say, I like about 200, I want to be able to know everybody.

What is interesting about Stanley’s comments as they applied to youth ministry is that he clearly feels young people need their own company-sized groups in order to thrive. For a church youth group to have around 150 members then it is probably necessary to have a church that operates at numbers equivalent to the battalion or regiment. And a church of that size will then need to organize its members into company and platoon sized groups if they are to ‘stick’. A church of this numerical strength has the advantage of being able to program for different groups in a very deliberate and targeted way. The disadvantage is that this can tend to create very homogenous groups, and arguably simply ape our consumer culture. It is this advantage/disadvantage that lies at so much of the tension between the attractional-mega-church model, and the incarnational-missional-church model.

Speaking from personal experience, as a teenager I attended a small church with a small youth group. The downside of this was a certain feeling of social isolation, but it also helped me to be focused about following Jesus – I knew I had to stand on my own two feet when it came to my faith. Then, when I was 16, my family moved to another town, and a large church with a big youth group. At first this was great, as suddenly I was part of a crowd of teenagers who all seemed to be pursuing Jesus. But within a few months, rather than encouraging one another in our faith, most of us had encouraged one another out of it as we all ‘backslid’ together. I don’t blame the church at all for that – it was our responsibility – but it is at least anecdotal evidence that a large youth group does not necessarily lead to spiritually healthy young people. If anything, being part of a large youth group increased our sense of not needing the other members of the church, though we might have been healthier if we had.

The church I now lead (by Stanley’s measure) is small, with a small youth group. I’d love both the church and the youth group to be larger. It’s certainly not me being ‘stinking selfish’ that lies behind our numerical size. But I do think Robin Dunbar probably had a better insight into how human community functions best than do some mega-church pastors.